The thirteenth of April this year marks the 100th anniversary of the Jallianwala Bagh (Amritsar) massacre. To understand, and appreciate, its significance in the struggle of the Indian people for liberation from British colonial rule, it is important to put it in the context of the first imperialist world war, fought between two coalitions of imperialist bloodsuckers to redivide the world.

Euphemistically referred to as the Great War by imperialist statesmen and historians alike, it was the first industrial-scale slaughter of tens of millions of workers in order to decide which of the bandit gentries would have what share of the booty – of markets, resources, avenues for investment and colonial slaves.

On 4 August 1914, Britain entered the war against the German-led coalition. Simultaneously, Lord Hardinge, Viceroy of India, made a declaration of India’s entry into the war on Britain’s side. The Indian people were neither consulted nor had any interest, any more than did the workers elsewhere, in participating in the imperialist carnage into which, as subjugated people, they were dropped willy-nilly, and for which they paid a high price in blood and treasure.

By the end of the war, 1.4 million Indians had been enlisted to serve. Of these, 74,000 were not to return. Indian servicemen, like servicemen from other colonies of Britain, had to fight in harsh and unfamiliar conditions in Europe. As Britain did not have sufficient soldiers to fight in both Europe and the middle east, Indian soldiers were deployed in large numbers in the middle-eastern theatre of war.

On 1 May 1915, sikhs and Gurkhas of the 29th Infantry Brigade landed on the Gallipoli peninsula to join British, Australian and New Zealand troops in what was to turn out to be an ill-fated operation to gain control of the Dardanelles strait, capture Istanbul and drive Turkey out of the war. On 4 June, their comrades of the 14th Sikhs were virtually annihilated.

If Gallipoli was a serious defeat, Britain’s other campaign against the Turks in Mesopotamia (now Iraq) was to turn into a calamity – the battle of Kutt, where General Charles Townshend’s army was encircled by the Turks. On 29 April 2016, with relief failing to materialise and his supplies exhausted, Townshend surrendered his 13,000 men into bitter captivity. It was the worst military disaster to befall the British empire since the 1842 retreat from Kabul.

The report of the commission of enquiry into the Kutt defeat, published in 1917, was so scathing that the secretary of state for India, Conservative Austen Chamberlain, resigned and was replaced by Edwin Montagu.

By 1916, the middle east had become the Indian army’s principal theatre of operations. The campaign that took Baghdad on 11 March 1917 and then advanced to Mosul and Kirkuk would not have been feasible without Indian troops. So, too, Sir Edmund Allenby’s advance into Palestine and Syria in 1918.

On top of the losses of life, India’s material contribution to the war effort was colossal.

That alleged apostle of non-violence, Mahatma Gandhi, when he arrived in London on 5 August 1914, immediately set about establishing an Indian ambulance corps. Bal Gangadhar Tilk, the scourge of the British Raj, newly released from six years’ imprisonment in Mandalay, pledged support for the British government, as did the Indian National Congress at its sessions in 1914 and 1915.

The rulers of the princely states, ever the flunkeys of the Raj, were likewise more than willing to render generous support. Many of them, to express their loyalty, sailed to the fighting fronts, including the European theatre. The Maharaja of Patiala, Bhupinder Singh, had been made an honorary Major General by the end of the war.

India’s reward

At the Paris peace conference India was represented by Lord Montagu and the Maharaja of Bikaner, who signed the Versailles Treaty on its behalf.

The war, however, had radicalised politics everywhere, India included. The ripples of the earth-shaking Russian revolution were spreading around the world. Indians expected to be rewarded for their war effort.

On 20 August 1917, Montagu made stated in the British parliament that the government’s policy was “the progressive realisation of responsible government in India as an integral part of the British empire”. What did this mean? Montagu toured India in the winter of 1917-18, and it fell to him and the viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, to meet Indian expectations.

The report that embodied the conclusions of the secretary of state was made public on 8 July 1918. It proposed a new legislative assembly of 100 members, two-thirds of them to be elected, but endowed with no real powers. The crux of the scheme was a new arrangement for the provinces that went by the name of dyarchy or dual government, whereby the British would retain certain functions, with elected Indian ministers allotted some authority over others.

The report, which disappointed all sections of public opinion, was a slap in the face to India after all her sacrifices in the war effort on Britain’s behalf – an effort allegedly in defence of British liberties while Britain was denying the most elementary freedoms to the Indian people.

More than that. During the war, colonial rule had been challenged by revolutionary movements in Punjab (the Ghadarites) and Bengal, delivering a blow to the confidence of the alien rulers.

The British had managed cruelly to suppress these through the draconian provisions of the 1915 Defence of India Act, which was set to expire at the end of the war. However, a committee under the chairmanship of Justice Sydney Rowlatt in 1918 recommended the extension of this repressive legislation into peacetime.

It was an outrage to public opinion in India that the only reward for the country’s sacrifices was to be further repression.

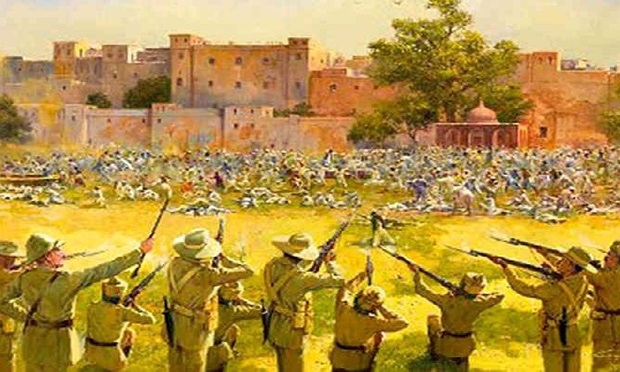

Amritsar massacre

It is in this context that the Amritsar massacre must be viewed. At its December 1918 session, the Indian National Congress (INC) not only rejected the Rowlatt report, but also dismissed the Montagu-Chelmsford report as unsatisfactory. The 1918 session of the INC, held in Delhi, also decided that its next annual session would be held in Punjab.

As the Punjab was the largest source of recruits for the British imperial army, the British authorities were determined to prevent the state’s politicisation, especially in view of the rising nationalist sentiment among the population and sections of the army. On no account would the authorities tolerate any activity that might undermine their recruitment activities. Consequently, they determined to prevent the Congress session from being held in Punjab.

Dr Saifuddin Kitchlew, a prominent advocate in Amritsar (a Punjabi city and the holy centre of Sikhism), and Dr Satpal, a medical practitioner in Lahore (the capital of all Punjab before the partition of India), took up the challenge and began organising the Congress session, to which the authorities took serious exception.

The Freedom movement, inspired by the activities of the Ghadar party (born in the US and Canada, principally thanks to immigrant sikh workers in 1913-14), and outraged by the brutal repression visited on the Ghadarites by the British authorities, had struck deep roots in Punjab.

At the same time, the authorities introduced the draconian Rowlatt legislation, which gave power to a court of three judges to punish those involved in revolutionary activities, with no right of appeal. Anyone even suspected of involvement with the Freedom movement was liable to be detained under its provisions.

Gandhi called for a protest, to be staged on 30 March 1919. On this day, the police fired on protesters in Delhi, killing five people and injuring several hundreds – an action which sparked countrywide protests and demonstrations.

These protests notwithstanding, the authorities doubled down on their policy of repression. They arrested Dr Kitchlew and Dr Satpal and whisked them away to some unknown destination on 10 April. This in turn gave rise to fierce and angry protests, with a large crowd heading in the direction of the office of the district magistrate in Amritsar demanding the release of their detained leaders. Once again, the police wantonly opened fire on the crowd, killing several people.

Not unexpectedly, the outraged crowd targeted officers and official buildings alike. The situation got so out of hand that the authorities, unable to handle the protests, handed over Amritsar, and soon after the whole of Punjab, to the military, instituting a de facto martial law.

It was against this backdrop that a large public gathering was arranged in Jallianwala Bagh, with prior notice. Approximately 20,000 men, women and children who were in Amritsar for the major Baisakhi festival arrived for a peaceful meeting.

As the meeting got under way, suddenly, as if out of nowhere, British General Reginald Dyer entered the arena, blocked the only exit route, and gave the order to his men to fire. The shooting only stopped when the troops ran out of ammunition, having fired 1,600 rounds.

According to official estimates, this wanton act of brutality resulted in 400 deaths and in injuries to more than 2,000 people. A more correct estimate, however, was produced by the independent commission of enquiry appointed by the INC. This commission furnished documentary evidence which made it clear that more than 1,000 people had been murdered while another several thousand were injured consequent upon the firing by General Dyer’s mercenary assassins.

Dyer’s cynical defence of his brutality

Following a public outcry, the British government appointed the Hunter committee to enquire into the shooting, while at the same time continuing with its terrorisation of the population, cutting off the water and electricity supplies to the town and publicly flogging anyone perceived to be sympathetic to the victims of the massacre.

Far from showing any remorse, General Dyer, in his deposition to the Hunter committee, justified the massacre of peaceful innocent people, admitting that he had ordered the shooting without warning to the crowd to disperse. In his report to the General Staff Division on 25 August 1919, he stated:

“I fired and continued to fire till the crowd dispersed, and I considered that this is the least amount of firing which would produce the necessary moral and widespread effect it was my duty to produce if I was to justify my action. If more troops had been at hand the casualties would have been greater in proportion. It was no longer a question of merely dispersing the crowd but one of producing a sufficient moral effect, on those who were present, but more especially throughout the Punjab. There could be no question of undue severity.”

Dyer stated that he intended “to strike terror into the whole of Punjab. I had made up my mind that I would do all men to death if they were going to continue the meeting.”

A final nail into the coffin of the British Raj

During their 190 years of rule in India, the British committed countless massacres and perpetrated unheard of infamies and cruelties, especially during the course of suppressing the First War of Independence in 1857-59.

During British rule, more than 30 million Indians died in largely manmade famines, including the notorious Bengal famine during the second world war, which claimed the lives of between three and five million people.

But the Amritsar massacre, because of its timing and circumstances, electrified the Indian people and became a turning point in the long struggle of the Indian people for liberation.

Not just Punjab but the whole of India was in uproar. The authorities were unable to block the Congress session from being held in Amritsar, from where Gandhi launched the first of his disobedience movements.

The brutality unleashed by the government only served to strengthen the unity of the Indian people and their determination to free India from the clutches of the hated British rulers. No amount of repression, brutality and bestiality could deter them any longer.

It is no exaggeration to say that the Amritsar massacre drove the final nail into the coffin of British imperialist rule in India.

Tagore renounces knighthood

Rabindranath Tagore, the country’s most famous writer, poet and a foremost intellectual, who had earlier entertained illusions about the benign intentions of the British, had his eyes opened. He renounced the knighthood conferred on him by the British monarch.

Here are excerpts from his letter of 31 May 1919 to the viceroy:

“The disproportionate severity of the punishments inflicted upon the unfortunate people and the methods of carrying them out, we are convinced, are without parallel in the history of civilised governments …

“The accounts of the insults and sufferings undergone by our brothers in the Punjab have trickled through the gagged silence, reaching every corner of India and the universal agony of indignation roused in the hearts of our people has been ignored by our rulers – possibly congratulating themselves for what they imagine as salutary lessons …

“The very least I can do for my country is to take all consequences upon myself in giving voice to the protest of the millions of my countrymen, surprised into a dumb anguish of terror. The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part wish to stand shorn of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen who, for their so-called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings.”

Udham Singh avenges the massacre

It was to avenge the Amritsar massacre that, 21 years later, Udham Singh, who as a 15-year-old orphan had witnessed the carnage, shot dead on 13 March 1940 Sir Michael O’Dwyer who at the time of the slaughter in Amritsar had been Lt Governor of Punjab (General Dyer had already died in 1927). The shots that rang out at Caxton Hall, London, brought joy to the Indian masses, but not to that apostle of non-violence Gandhi, who condemned Udham Singh’s actions as that of a madman.

Appearing in court, charged with the murder of Sir Michael O’Dwyer, Udham Singh gave his name as Ram Muhammad Singh Azad, thus emphasising the unbreakable bonds of unity between the people of India – hindu, sikh and muslim. Frankly admitting to the murder of Sir Michael, Udham Singh made a statement in court in which he said:

“I did it because I had a grudge against him. He deserved it. He was the real culprit; he wanted to crush the spirit of my people, so I have crushed him. For a full 21 years I have been trying to wreak vengeance. I am happy I have done the job. I am not afraid of death.

“I am dying for my country. I have seen my people starving in India under the British rule. I have protested against this. It was my duty. What greater honour could be bestowed on me than death for the sake of my motherland?”

In another section of his statement, Udham Singh made clear that he had nothing against the British people, only against their ruling class.

These are not the words of a madman, but those of a passionate patriot and an internationalist.

On 31 July 1940, Udham Singh was hanged at Pentonville prison in London. His remains are preserved at Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar and visited by tens of thousands of people every year.

The great revolutionary and internationalist Bhagat Singh, too, visited the site of the massacre in Amritsar, which made a lasting impression on him and on a whole generation of revolutionaries, whose contribution to the freedom struggle of the Indian people continues to be ignored by the despicable ruling classes of India for the simple reason that Bhagat Singh and his fellow revolutionaries wanted an India free not just from the British rulers but also from all exploitation of man by man.

This is not a message that suits the present-day rulers of India, but it does resonate with the vast masses of workers and peasants, the downtrodden and the destitute, who continue to draw inspiration from these heroes of Indian freedom, and for whom the Jallianwala Bagh continues to be a symbol of resistance against all oppression and a pledge of a brighter future.

On the 100th anniversary of this heinous act perpetrated by British imperialism, we salute in respectful homage all those who have shed their lives in the struggle to free India from foreign rule as well as from all exploitation. At the same time, we condemn most resolutely the author of this tragedy – British imperialism.

It has ever since been the demand of the Indian people, as well as of progressive opinion everywhere, that the British government must offer an official apology for this slaughter of innocent peaceful protesters on that fateful day in 1919. Even if belated, such an apology would go some way towards assuaging the feelings of bitterness felt by the Indian masses.